For an Informed Love of God

You are here

Apposition and Word Order (Acts 3:20)

Sometimes we have to change the order of words to accurately convey the meaning of a Greek sentence, and sometimes this is because of how Greek can pile up modifiers.

Apposition can be a bit of a bear to bring into English. Take Acts 3:20 for example. Peter is calling the people to repent so their sins can be forgiven, so times of refreshing can come, and so that “He might send the appointed to y’all Christ Jesus” (ἀποστείλῃ τὸν προκεχειρισμένον ὑμῖν Χριστὸν Ἰησοῦν).

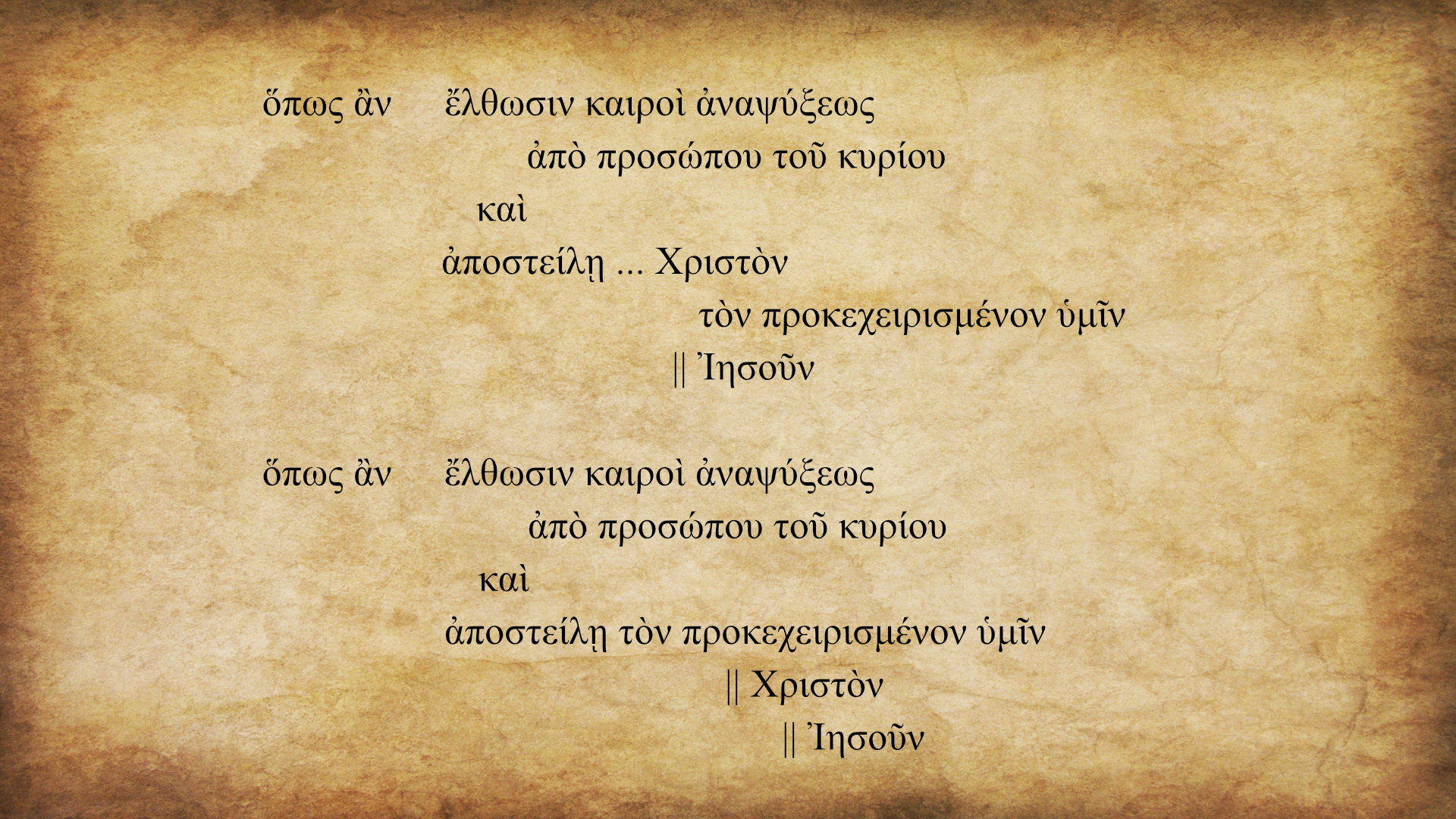

Most translations read Χριστόν as the direct object of ἀποστείλῃ and Ἰησοῦν as being in apposition to Χριστόν, and in Greek word order this is easy to see because Χριστόν and Ἰησοῦν are right next to each other. But when you translate the modifier προκεχειρισμένον ὑμῖν, it pulls the translation of Χριστὸν away from Ἰησοῦν, which then makes it difficult to identify apposition in English: “... he might send the Christ who has been appointed for y’all, Jesus. So how do you indicate apposition?

If Luke wouldn’t mind, I would like to rearrange his Greek: ἀποστείλῃ Ἰησοῦν, τὸν χριστὸν, προκεχειρισμένον ὑμῖν. “He might send Jesus, the Christ who has been appointed for y’all.” Rearranging the word order makes apposition easy to translate into English, and it is actually what the NASB does, does the KJV. (“He shall send Jesus Christ, which before was preached (προκεχειρισμένον) unto you.”)

You can see the translations struggling with this. The ESV relies on punctuation, which doesn’t help the person reading out-loud: “he may send the Christ appointed for you, Jesus.”

The CSB changes the Greek so it isn’t in apposition: “that he may send Jesus, who has been appointed for you as the Messiah.”

The NET is even more awkward and difficult to read out loud: “so that he may send the Messiah appointed for you—that is, Jesus” (also the NRSV but without the dash).

The NLT translates Ἰησοῦν as if it were the direct object. It’s not, but it does convey the meaning well. “He will again send you Jesus, your appointed Messiah.”

Of course, there is a simpler way to read the Greek, and that is to see τὸν προκεχειρισμένον as the direct object of ἀποστείλῃ, and that makes Χριστὸν Ἰησοῦν in apposition to προκεχειρισμένον. Frankly, I am not sure why translations don't do this. It is simpler and straight forward Greek. “He might send the appointed one to y’all, Christ Jesus.” If you wanted to translate “Christ” as “Messiah,” then you would want to make sure that Ἰησοῦν is clearly in apposition to Χριστὸν. “He might send the appointed one to y’all, the Messiah, who is Jesus.”

The fact of the matter is that you can’t go word-for-word, and I think the best thing to do here is to rearrange the order of words as the NASB does. But isn’t it interesting that the most formal equivalent translation of the bunch becomes dynamic to convey meaning? And it again illustrates that you can’t rely on English translations to see the underlying Greek structure unless you already know the Greek.

Comments

"Jesus" and "Christ" in apposition