For an Informed Love of God

You are here

Literally, There is No Such Thing as Literal

I am starting a short series of blogs on what I have learned about translation since joining the Committee on Bible Translation, which controls the text of the NIV. In this first posting I am discussing my dislike of the word "literal."

I have learned that the word “literal” should be banned from all discussion of translation. Most of the time its use assumes the conclusion. Someone will say they want a “literal” Bible, by which they mean word-for-word, which they then assume means accurate. By their very definition of the term “literal,” the conclusion of the debate is assumed. The problem is that this simply is not what the word “literal” means.

The basic meaning of “literal” has to do with meaning, not form. It denotes the actual, factual meaning of something, “free from exaggeration or embellishment” (Merriam-Webster). The American Heritage Dictionary defines “literal” as, “Being in accordance with, conforming to, or upholding the exact or primary meaning of a word or words. Word for word; verbatim. Avoiding exaggeration, metaphor, or embellishment.” Hence, a “literal” translation is one that is faithful to the meaning of the original author, using words with their basic meaning, not exaggerating or embellishing the original meaning.

The Oxford English Dictionary’s primary definition of literal is: “Free from metaphor, allegory, etc.... Theol. Originally in the context of a traditional distinction between the literal sense and various spiritual senses of a sacred text: designating or relating to the sense intended by the author of a text, normally discovered by taking the words in their natural or customary meaning, in the context of the text as a whole, without regard to an ulterior spiritual or symbolic meaning.”

Notice the emphasis on meaning, not form. “Literal sense” vs. ”spiritual sense.” “Customary meaning.” Understanding a word “in the context of the text as a whole.” Opposed to a “symbolic meaning.” Nowhere in this definition do you find anything akin to form, to thinking that a literal translation would translate indicative verbs as indicative, or participles as dependent constructions. “Literal” has to do with meaning, not form.

The American Heritage Dictionary has the example, “The 300,000 Unionists ... will be literally thrown to the wolves.” Of course, the speaker “literally” does not want the Unionists to be torn apart by animals. Another dictionary speaks of “fifteen years of literal hell,” but that does not mean “hell‚” at least, not “literally.”

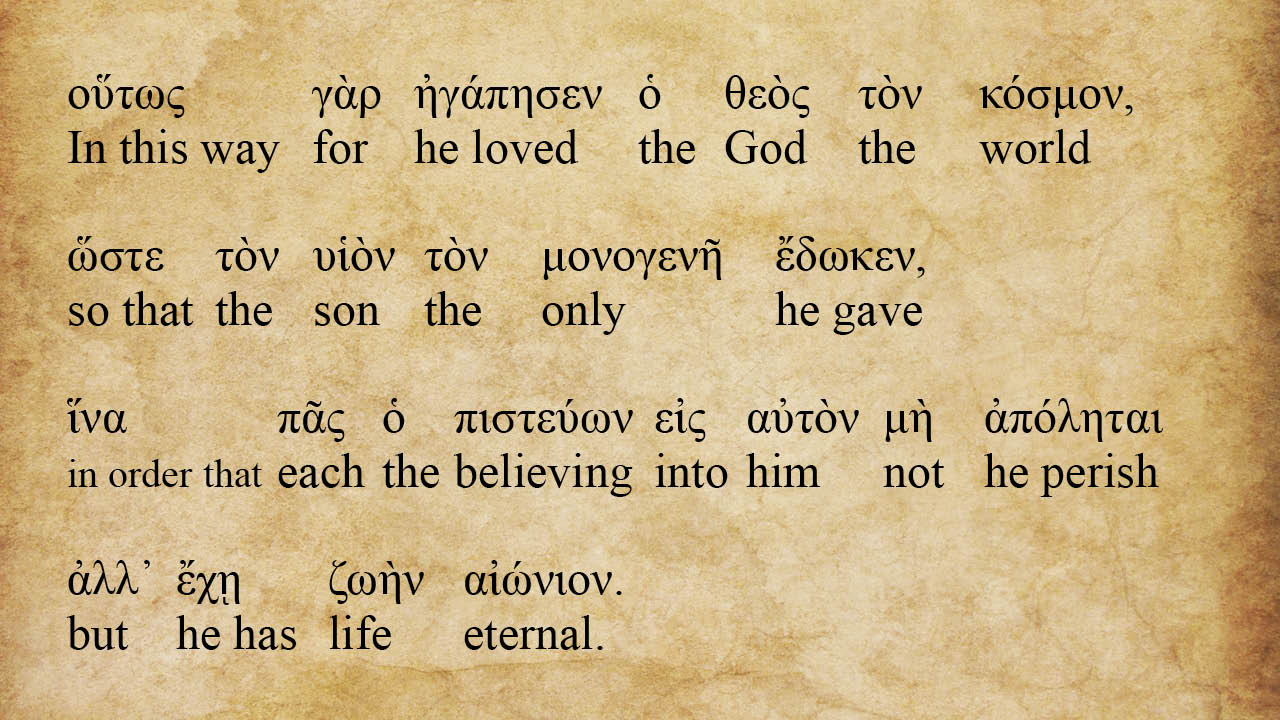

If we were to follow the definition of “literal” often used in discussions of Bible translation, then none of us would read English Bibles; instead, we would be reading interlinears. We would turn to John 3:16 and read, “In this way for he loved the God the world so that the son the only he gave in order that each the believing into him not he perish but he has life eternal.” These are the English words that represent the Greek words. But no one thinks this is translation, so why would someone ask for a “literal” translation of the Bible? Any publisher who advertises that their Bible is a “literal” translation should only be selling interlinears.

My friend Mark Strauss, also on the CBT, makes the point that even a word does not have a “literal” meaning but rather what we call a “semantic range.” I like to refer to words as having a bundle of sticks, with each stick representing a different (but perhaps related) meaning. Certainly, one of the sticks may be larger than the rest, representing the more frequently used meaning of the word or what we teach in first-year Greek as the “gloss,” but it is only one among many. So if you were producing a “literal” Bible, how would you find the literal meaning of a word? A first-year Greek gloss, perhaps, but not the meaning of the word.

Mark uses the example of the word “key.” What does “key” “literally” mean? The answer is that it has no “literal” meaning. It has no core meaning. There is no big stick in its bundle. “Did you lose your key?” “What is the key to the puzzle?” “What is the key point?” “What key is that song in?” “Press the A key.” “He shoots best from the key.” “I first ate key lime pie in Key West in the Florida Keys.

So what is the “literal” meaning of the Greek word sarx? The NIV (1984 version) has been heavily criticized for translating sarx as context requires, but even the ESV uses 24 different English words to translate this one Greek word. The Greek word sarx has no “literal” meaning. Its main non-figurative use may be “flesh,” its biggest stick in its bundle. But why would we think that “flesh” is its literal meaning.

This is why it is impossible to bring all the nuances of the Greek and Hebrew into English. Words are much too rich in meaning to be encapsulated into a single gloss. The more functional the translation, the easier it is to bring more of the meaning over. Jesus is our hilasmos, our “propitiation” (NASB), “expiation” (RSV), but the NIV helps the reader by being a little more explanatory by using “atoning sacrifice,” and the NLT says “sacrifice that atones for our sins” (1 John 2:2). For formal equivalent translations like the NASB or ESV, nuances will by necessity be lost.

You can expand this argument concerning the word “literal” by looking at metaphors. What is the literal meaning of a metaphor? No one argues that every metaphor should be translated word-for-word because that would generally be meaningless. But that is the point. What is the primary criteria that controls our translation? Is it attention to form, or meaning, that creates an accurate translation? The fact that metaphors almost always need to be interpreted shows that meaning is primary to form.

We would never say “cover your feet” for using the toilet, or “having in the womb” for being pregnant. I was teaching in China several years back and talked about “straddling the fence.” I stopped and asked my translator how she handled that idiom. Turns out there is a similar (but not exact) idiom in Mandarin about having each foot on a different boat. But most idioms do not have even approximate equivalents and hence cannot be translated word-for-word.

Translating idioms is almost impossible for any type of translation, but especially for a Bible claiming to be “literal.” In order to say that God is patient, Hebrew says that he has a “long nose,” brought into the KJV with the phrase “long suffering.” But the Hebrew author never meant to convey the idea that God has a protruding proboscis. It is an idiom, which means that the meanings of the individual words do not add up to the meaning of the phrase. In other words, it would be misleading to translate just the words; we have to translate the meaning conveyed by the words.

The same argument can be made with non-idioms such as a genitive phrase. Hebrews 1:3 says that Jesus “upholds all things by the word of his power.” This is basically word-for-word what the Greek says (φέρων τε τὰ πάντα τῷ ῥήματι τῆς δυνάμεως αὐτοῦ). The problem, of course, is that the translation doesn’t mean anything. I could understand “the power of his word,” but not the reverse. δυνάμεως is clearly an Hebraic genitive and hence the NLT translates, “he sustains everything by the mighty power of his command.” A “literal” translation would produce a meaningless phrase if all it did was translate words.

One of the truths that I have learned since coming on the CBT is that the word “literal” should never be used in a discussion of translation because it is so readily misunderstood. But if used, it should be used accurately. A “literal” translation has very little to do with form. A “literal” translation is one that conveys the meaning of the original text into the receptor language without exaggeration or embellishment.

Comments

Accuracy

Thank you!