For an Informed Love of God

You are here

Formal Equivalent Translation Theory

"Formal Equivalent Translation" try to translate word-for-word as much as possible, and shift to translating meaning when necessary. This gives the impression of being an "accurate" translation. But the simple fact of the matter is that no translation goes word-for-word in a single verse in the Bible. The nature of language doesn't allow it.

Formal equivalent translations try to reflect the formal structures of the original text, making the translation “transparent” to the original. This means translating indicative verbs as indicative, participles as participles, and trying to use the same English word for the same Greek word if possible (“concordance”). When it makes no sense to translate word-for-word, the translators ask what the verse means, and then how can they convey the same meaning while adhering as closely as possible to the formal Greek structures? The ESV, NASB, and KJV fall into this camp.

The problem is that this admission — that meaning is primary to form when the words have no meaning in and of themselves — is itself a refutation of the basic tenet of formal equivalence. If the meaning of the sentence is the ultimate criterion, then meaning becomes the ultimate goal of translation. It may give some people comfort to think that their translation reflects the underlying Greek and Hebrew structures, but if they don’t know Greek and Hebrew then they can’t know when the translations in fact do reflect that structure. In every single verse, there will be differences between the Greek and the English. All translations are interpretive.

The fact of the matter is that there is not a single verse in the Bible that goes word-for-word. The differences in vocabulary and grammar simply do not allow this. No one translates ho theos as “the God.” Rather, they all drop out the article ho, add in a preposition “of,” and then have to decide whether to write “God” or “god” for theos. No translation translates every initial conjunction in a sentence. No translation always indicates the expected answer of a question prefaced with ou or mē. No Bible translation goes word-for-word.

Concordance

By staying as close as possible to the Hebrew and Greek words, formal equivalent translations carefully honor the dividing line between translation and commentary. This is commendable, as is the attempt to provide concordance to the English reader.

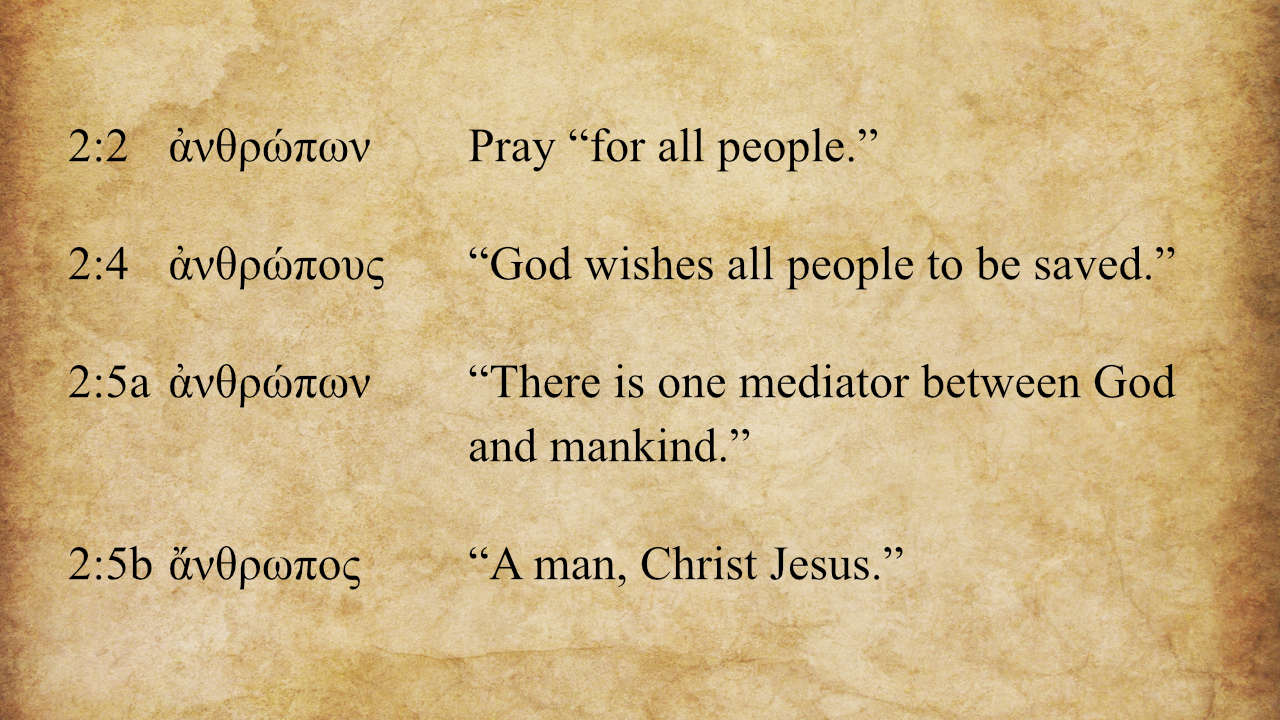

But concordance can be tricky. One of the most difficult passages to translate is 1 Timothy 2:17 because we no longer have the word to translate anthrōpos, often translated as “man” or “mankind,” which Paul is using to tie the passage together. Paul’s basic argument is that the Ephesians should pray for all “men” (v 2) because God wishes all “men” to be saved (v 4), and there is only one mediator between God and “men,” the “man” Christ Jesus (v 5). Only the NASB keeps the concordance, but thereby suggests to some modern readers that v 2 says the Ephesians should pray for all males. Even the ESV, which has a strong commitment to concordance, translates πάντων ἀνθρώπων as “all people” (v 2) with a footnote on verse 5. But God wants all people to be saved, not just all men, and the point is not that Christ Jesus is a male but that he is part of humanity.

Another issue with concordance is that it can place too much weight on one gloss of a word and can thereby mislead. The NASB translates polis every time as “city.” This is helpful for the informed English reader watching for concordance, but the “city” of Nazareth was no more than a wide spot in the road inhabited by 600 people and hence the practice misinforms. Nazareth was a “town,” not a “city.”

Teachers know that sarx occurs 147 times in the Greek Testament and is translated 24 different ways in the ESV (excluding plurals). We know that logos occurs 334 times and is translated 36 different ways by the NASB. These examples demonstrate that concordance may be an ideal for which to strive, but it is frequently impossible to achieve.

It is often said that translations should honor the syntax of the Greek, or what is called “syntactic correspondence.” If God inspired the author to use a participle, then we should use a participle. If God inspired a prepositional phrase, we should not turn it into a relative clause. The problem of course is that in reality not a single translation does this. Every single one abandons syntactic correspondence when necessary to convey meaning.

We see this for example when syntax is changed to complete an anacoluthon such as 1 Tim 1:3. Both the NASB and the ESV change the participle προσμεῖναι to an imperative. “As I urged you upon my departure for Macedonia, remain on at Ephesus.”

I favor syntactic correspondence when it accurately conveys meaning. I especially want to know when a verbal form is dependent or independent. But the point of translation is meaning, and sometimes meaning is best conveyed with different parts of speech and different grammatical constructions.

Inspiration

Some claim that formal equivalent translations have a higher view of inspiration, recognizing each word as a word from God and hence worthy of translation.

When modern translators do not know for sure what a word or phrase means, I agree that there is value in simply translating the words and leaving interpretation up to the reader. We do not know what “Selah” means in the Psalms, but most translations still include it.

However, an insistence on translating every Greek and Hebrew word shows a defective view of language and how it conveys meaning. My view of “verbal plenary inspiration” means that the meaning conveyed by every word is from God and should be reflected in the translation; however, if inspiration applied only to the words, then none of us would or should be reading English Bibles since those inspired words are in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

Consider the story of the prodigal son. When the father saw his prodigal son returning, he ran and “fell on his neck” (KJV, Luke 15:20). While that is a word-for-word translation, it certainly is not what the text means. Even the NASB, the most formal equivalent translation in English, says that the father “embraced” him, with the footnote, “Lit fell on his neck.” If that is what it literally means, then why not translate it as such? The NET’s footnote is much better: “Grk ‘he fell on his neck.’” The idiom means the father “embraced” (ESV, NLT) or hugged his son (NET). The NIV is clever in preserving the idiom in an understandable way; “threw his arms around his neck” (also CSB).

A translation should make sense, written in the vernacular of the receptor language. Meaning can be conveyed by a word, but usually it is conveyed by a group of words. Insisting that formal equivalent translations have a higher view of inspiration reflects a defective view of how language conveys meaning.

For my fuller paper on this topic, click here.

Comments

Agreed!